CORRAL HOLLOW COAL MINES

Corral Hollow Coal Discovery

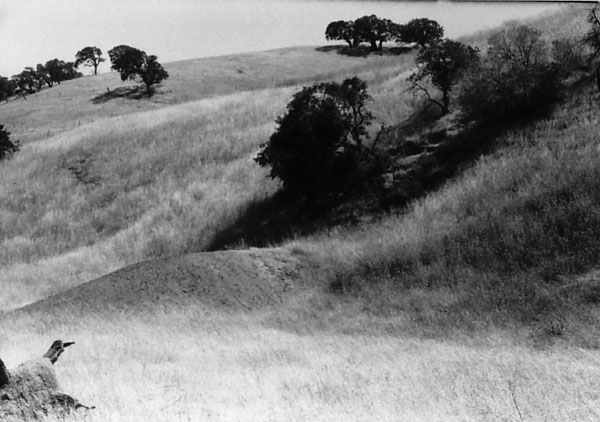

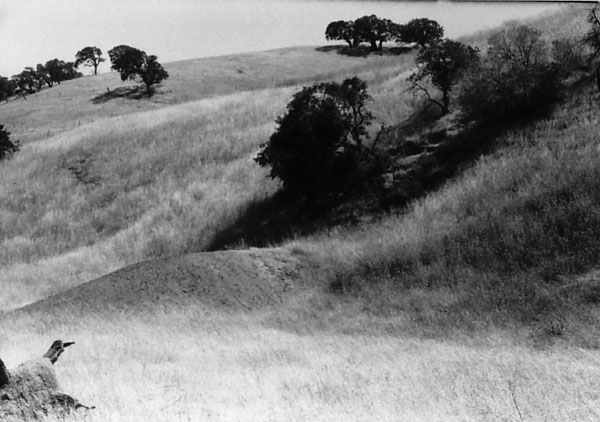

Site of the first discovery of coal on the north bank of Corral Hollow Creek. The dark gray

material is coal. The Coast Range Coal Company labeled this "A" on its prospectus map.

Coal was discovered in Corral Hollow in November 1855, when a crew of railroad surveyors, led by Francis O'Byrne, was

staking a proposed line of the San Francisco and Stockton railroad, which was to run between Oakland and Stockton.

The surveyors were on the banks of Corral Hollow Creek at the confluence of the creek issuing from Baker's Ravine, where

Tesla Road presently enters Corral Hollow in Alameda County, California. The coal was discovered when one of the surveyors was putting a stake into

the bank of Corral Hollow Creek. Several showings of coal were found in the eroded banks of Corral Hollow Creek and the

coal ledge was traced to a sandstone bank where the seam was vertical. The coal ledge was reported to be one

to five feet in thickness and was traced for over two miles. News of the Corral Hollow coal discovery was reported in

newspapers throughout the state. The surveyors immediately recorded their coal claims at Stockton and Benicia.

Advertisement for the Coast Range mine.

California Coast Range Coal Mine

Two San Francisco businessmen, Alfred Wheeler and Frederick Marriott, purchased the claims from the surveyors for $4,000.

Thus was born the first coal mining company to form in California, which they called the California Coast Range Coal Mining Company,

which filed its articles of incorporation on January 7, 1856. The capital stock of $100,000 was divided into 1,000 shares, which

was sold at $100 each.

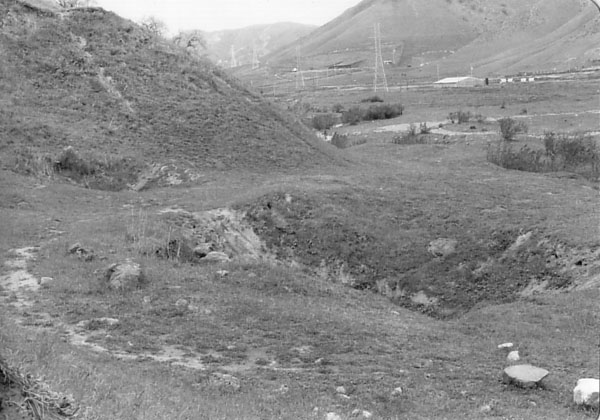

Remnants of Baker's shaft, Coast Range coal mine, which was labeled "B" on the company's prospectus map.

They claimed 640 acres of land stretching from the discovery point at the mouth of Bakers Ravine eastward about two miles into the

mouth of Mitchell Ravine. A mine shaft was sunk at the mouth of Bakers Ravine and this was to become the Coast Range coal mine, also

known as Baker's shaft. Lafayette C. Baker, who later was appointed to head the Secret Service by President Lincoln and for whom the

nearby ravine was named, was in charge of this mine. The crew of miners removed about 60 tons of coal from this shaft. The coal was

shipped by mule-team wagons to Slocum's Ferry on the San Joaquin River, where it was transferred to river scows and sent to Stockton,

where Scofield & Keeler had a coal yard. The coal was sold at $15 per ton, making this the first commercial coal mine in California.

When the shaft reached a depth of about 60 feet, the coal pinched out. The miners searched frantically for the lost coal by driving

galleries in three directions, but to no avail.

Baker then directed his miners to search for coal in a steep ravine on the west end of their claim. This ravine was to become

known as Old Tunnel Ravine, where Baker and his crew of miners drove an adit 180 feet into the hillside to successfully strike

a five-foot thick coal seam. But before Baker could develop this mine, he was called away to manage the coal yard in Stockton.

Other prospects were opened on thinner seams of coal down the canyon. By April 1856, the company was $26,601 in debt and called

for a suspension of operations. The first commercial coal mine in California was closed after only three months of operation.

Remnants of the Coast Range prospect adit labeled as "C" on the company's prospectus map.

Remnants of Baker's tunnel in Old Tunnel Ravine. The tunnel was behind the tall pine tree.

Pacific Coal Mines

John O'Brien's property was just west of the Coast Range Company property and he watched the coal miners with great interest. O'Brien

was from County Cork, Ireland, and he and his wife Margaret were raising sheep. In 1852, they had pitched a tent on the site of what

later became the Tesla Hotel. Soon after Baker had abandoned his coal mine in Old Tunnel Ravine, O'Brien started to look for coal on

his own property. He searched in the steep, narrow ravine west of Old Tunnel Ravine, hoping to find the extension of the coal seam that Baker

had found nearby. Finding indications of what he thought was coal, he summoned his friends at the Zink House Tavern at the mouth of

Corral Hollow, Edward B. Carrell and Horatio Wright, to help him dig the shaft. High up in the ravine, the three men dug down on the

coal seam. When the shaft was 88 feet deep, they had uncovered the largest coal seam in the district, the 12-foot thick Eureka coal seam.

They traced the Eureka coal seam across the gulch to the west and followed it further in a drift, which they called the Upper Tunnel.

Remnants of O'Brien's shaft dug into the Eureka coal seam

that John O'Brien had discovered. Photo courtesy of Art Hull.

Remnants of the Upper Tunnel drift on the Eureka coal seam.

The mine entrance at the rear of the tailings pile is filled in.

In December 1856, Wright took samples of coal to Stockton to announce their discovery, which was reported by all of the newspapers.

O'Brien and Carrell next opened the Lower Tunnel on the 4-foot thick Livermore coal seam. They went into Old Tunnel Ravine to extend

Baker's tunnel 45 feet to strike the Eureka coal seam. Now the massive Eureka coal seam was proven over a length of 1,200 feet.

This attracted the attention of Henry C. Lee, proprietor of Lee and Bennett Circus, who offered to help develop the mines for a quarter

interest. David Howard, an associate of Lee and also a Mission San Jose merchant, got one-third interest in the mines when he offered

the labor of digging the tunnel, laying a rail, and building the coal bunkers, but Howard died before he could finish most of this work.

They secured a loan from Richard McClure, a merchant at Mission San Jose, to help pay for expenses. The Center Tunnel was dug to be the

main haulage tunnel as it intersected the center of the Eureka coal seam in Old Tunnel Ravine.

Remnants of the Lower Tunnel on the Livermore coal seam near

the oak tree in the center. Photo courtesy of Art Hull.

In February 1861, The Pacific Coal Mining Company was organized with the help of two San Francisco businessmen, Joseph S. Kohn and

Harmon Kozminsky. The capital stock was $500,000, divided into 1,000 shares that sold at $500 each. This company built coal bunkers and

laid tracks in preparation for production. Bunkhouses were built to board 25 to 30 miners. To quickly extract coal, a new drift, called the Lower

Mountain Tunnel, was driven west directly into the Eureka coal seam at a higher level above the rest of the mines in Old Tunnel Ravine.

The Pacific coal mines shipped and sold 400 tons of coal for $9 to 12 per ton. The coal was transported by

mule-team wagons to Mohr's Landing on Old River and then was taken by scows to San Francisco or Stockton.

Remnants of the Center Tunnel in Old Tunnel Ravine, with entrance still partially open.

The unusually heavy rains in November 1861 brought flooding that badly damaged the wagon road and this caused shipment of coal to cease.

By April 1862, the coal company was over $26,000 in debt, and foreclosure proceedings forced a Sheriff's sale of the coal property to

the highest bidder, Richard McClure, who was trying to recover his loan.

Alameda Coal Mines

In April 1861, Aurelius T. Ladd, a former coal dealer from San Francisco and brother of the founder of Laddsville (now Livermore), joined

the rush for coal in Corral Hollow and found some near the Alameda County line on the south bank of Corral Hollow Creek. Here he purchased 160 acres

of land from a former hunting partner of Grizzly Adams named Charley Foster. In October 1862, the Alameda Coal Mining Company

was organized with a capital stock of $500,000, divided into 5,000 shares at $100 each. The company spent $15,000 for a steam hoisting engine,

boilers, headframe, shaft house, and a bunkhouse. A vertical shaft was driven on a two-foot thick coal seam that was badly broken. It was

this shaft that William H. Brewer of the California Geological Survey had visited in October 1861, when he wrote, "the shaft is a miserable hole . . ." and

"Their work is folly - they never will get a profitable mine there." By 1864, the Alameda mine was abandoned.

Remnants of the Alameda mine, showing shaft house and mine

tailings before the Carnegie Park destroyed the site with a pond.

People Coal Mines

In 1867, Henry J. Booth, a proprietor of an iron works in San Francisco, was looking for cheaper fuel for his foundry.

He looked over the abandoned Alameda coal mine property and decided to give it a go. In August 1867, he organized the

Peoples Coal Mining Company, with a capital stock of $1,500,00, divided into 150,000 shares at $10 each. The company spent

$60,000 at the mine with a new shaft house, steam hoisting engine, and boilers. The old Alameda mine was widened and extended

to a depth of 310 feet. Gangways were driven east and west on the thin seam and crosscuts searched for new coal seams to

the north and south. The southern crosscut was driven 700 feet with no discoveries of coal!

Remnants of the Peoples mine tailings pile (formerly Alameda), which was turned into a pond by Carnegie Park.

The site of the Peoples 180-foot shaft, now buried by creek debris, is in the lower right corner of the photo.

A second shaft was sunk west of the Alameda mine on the north bank of Corral Hollow Creek. Here the shaft struck a thicker seam

of coal, which may have been an extension of the one that was worked in the Commercial mine further west. The shaft reached

a depth of 180 feet before the company was ordered to leave by Charles McLaughlin, who proclaimed to be the owner of the

odd-numbered section of land granted to him by the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 and 1864. They were on Section 29. If the

Peoples Coal Mining Company took out any coal, the quantity must have been small. The Peoples coal mine was abandoned and

the company was dissolved.

Commercial Coal Mines

In April 1862, Frank Sharp, Thomas Harris, Jenkin Richards, and David Hughs discovered coal near the mouth of

Mitchell Ravine on the south side of Corral Hollow. They dug a 200-foot deep shaft upon a six-foot thick seam of coal,

which was of the best quality in the district. In June 1862, the Commercial Coal Mining Company was incorporated with

a capital stock of $5,000, divided into 2,500 shares. The company spent $12,000 for a horse-whim, headframe, shaft house,

and a bunkhouse. Another smaller shaft was opened by C.T. Meader to a depth of 80 feet west of the main shaft. In 1863, about

200 tons of coal was shipped by mule-team wagons to Stockton and the mine was closed

temporarily by November 1863, when the company could not resolve the high cost of transportation.

Remnants of the Commercial mine tailings.

Remnants of the Commercial mine shaft.

With the coming of the Western (Central) Pacific railroad in 1868, there was renewed interest in the coal in Corral Hollow.

Coal from the Commercial mine was tested in the wood-burning locomotives and proved to be of such success that the railroad

company decided to convert their locomotives to coal-burning engines and extend a spur track to the mouth of Corral Hollow

from their main line at Ellis to receive the coal. The Commercial mine reopened in June 1869 with a large crew of miners.

They extended the shaft down to 300 feet in depth and was able to supply the railroad with 3,000 tons of coal. However, in

August 1870, the mine caught fire and had to be abandoned. The Commercial Coal Mining Company was dissolved shortly afterwards.

Remnants of the Meader shaft covered by brush.

Eureka Coal Mines

Richard McClure, a Mission San Jose merchant, who had acquired the Pacific coal mines in April 1862 at a Sheriff's sale to recover

a loan default by the former coal company, sold the coal property to John L. Taggard and William J. Adams. Taggard and Adams

took the contract to pay off the debts of the former coal company in an effort to acquire ownership of the mines. However,

they were not able to raise the needed funds and so the title, property, and interest reverted back to the Pacific Coal

Mining Company. That's when Peter Donahue, proprietor of the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, who was shopping for cheaper

fuel entered the picture. In May 1863, Donahue organized the Eureka Coal Mining Company, with a capital stock of $500,000,

divided into 5,000 shares. The Eureka Coal Mining Company purchased the title, rights, and interests of the Pacific Coal

Mining Company and proceeded to reopen the coal mines.

With a large crew of miners, several key mines were extended. The Upper Tunnel was extended to 740 feet and the Lower Tunnel

was extended to 446 feet in length along the Eureka coal seam. In Old Tunnel Ravine, the Lower Mountain Tunnel was extended

to 750 feet in length. In the process, over 400 tons of coal was removed and shipped to Donahue's iron works in San Francisco.

However, the cost of transporting the coal was more than Donahue had anticipated and he soon lost interest in the coal mines.

Remnants of the Lower Mountain Tunnel in Old Tunnel Ravine. Opening can be seen below

the road in the lower center of the picture. Eureka coal seam is the exposed brown

strata above the road. Bunkers on the extreme right are from a later quartz sand mine.

O'Brien, Carrell, Kohn, and Kozminsky kept the Eureka mines going, but they were only able to mine a few hundred tons of coal

before their money ran out. In March 1866, they borrowed $6,300 from San Francisco merchant William T. Coleman in an effort

to keep the company solvent. But six months later, they defaulted on the loan and Coleman became the new owner of the Eureka

coal mines, which he had to close. Coleman had his own financial troubles and he could never reopen the Eureka coal mines like

he had hoped to. He ended up selling them to John Treadwell in April 1890 for $40,000.

Tesla Coal Mines

Starting in the late 1880s, John Treadwell, a rich gold mine owner from Alaska, had quietly purchased all of the early coal mines

in Corral Hollow. In February 1895, he organized the San Francisco and San Joaquin Coal Mining Company, with a capital stock of $5 million,

divided into 50,000 shares that sold for $100 each. He hired 500 miners and built a company town named Tesla with over 200 buildings.

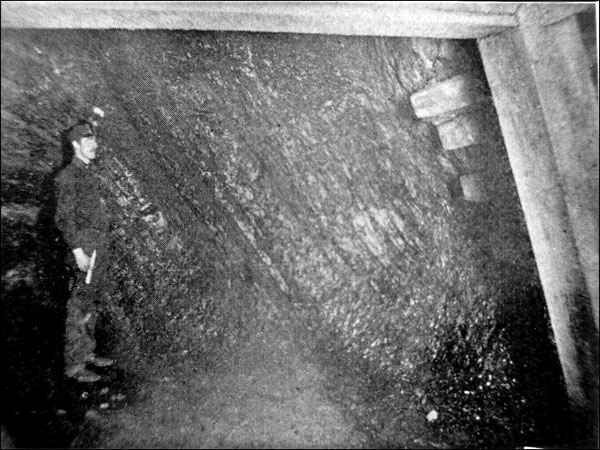

The Lower Mountain Tunnel was renamed Tesla Tunnel No. 1, and became the showcase of the Eureka coal seam for potential investors.

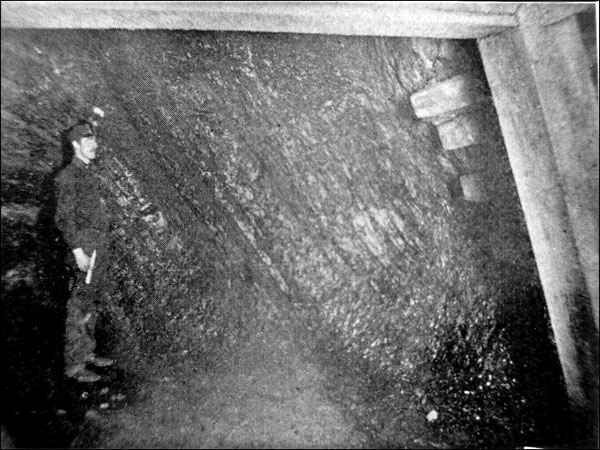

Underground view of the Eureka coal seam in Tesla Tunnel No. 1.

High up on the eastern side of Old Tunnel Ravine, Treadwell opened a new 800-foot deep inclined shaft, which was called Tesla Tunnel No. 2,

to develop the Eureka coal seam at deeper levels. On the western side of Old Tunnel Ravine, he dug a 3,000-foot long adit, which was called

Tesla Tunnel No. 3, which was to develop all three major coal seams in the district. Treadwell also extended the burned Commercial

coal mine to a depth of 500 feet.

Remnants of Tesla Tunnel No. 2, the main 800-foot deep shaft for the Eureka coal seam.

The shaft was behind the pine trees (left) on the hill and its tailings piles are on both sides.

Remnants of Tesla Tunnel No. 2, the main shaft, which is now a depression between the two trees.

In 1895, the company built a standard gauge railroad to the Stockton Channel in Stockton to transport the coal, and this became the Western

Pacific Railway in 1903, when they extended the line to Oakland. A coal briquette plant was erected next to the coal bunkers on the Stockton

Channel to make coal briquettes, the first to be sold successfully in the country. From 1897 to 1905, over 600,000 tons of coal was produced

from the Tesla coal mines. Coal mining ended in 1905, when a fire destroyed the coal briquette plant and adjacent coal bunkers at Stockton.

Thereafter, the company turned to sand and clay mining until those mines were closed in 1911, following a devastating flood on the property

compounded by the failures of the California Safe Deposit and Trust Company in San Francisco, which had financed these operations. The Tesla

coal mines were the last to produce coal from Corral Hollow.

Remnants of Tesla Tunnel No. 3, the 3,000-foot long haulage tunnel for all three major coal seams.

The tunnel portal was behind the small shack in the center, with its large tailings piles below.

Remnants of Tesla Tunnel No. 3, the 3,000-foot long haulage tunnel for all three major coal seams.

The portal of the tunnel was behind the small shack. The portal has been filled with rocks.

Sources

Mosier, Dan L., Corral Hollow Coal Mining District, Mines Road Books, Fremont, CA, 1983.

Mosier, Dan L., and Williams, Earle E., History of Tesla, A California Coal Mining Town, Mines Road Books, Fremont, CA, 2 edition, 2002.

Williams, Earle E., Carrell of Corral Hollow, Mines Road Books, Fremont, CA, 2nd edition, 2004.

Amazon affiliate link

Dan Mosier is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com

FTC Disclosure Statement:

Some links on this website may be affiliate links. We may get paid if you buy something or take an action after clicking one of these.

Contact Dan L. Mosier at danmosier@earthlink.net.

Copyright © 2014 Dan L. Mosier